STEVE COPE

LANDSCAPES IN THE PALM OF YOUR HAND

Steve Cope

Engineering time, space and place.

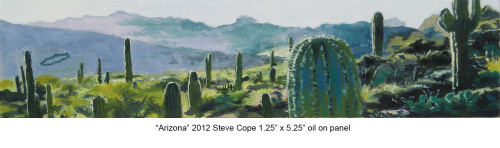

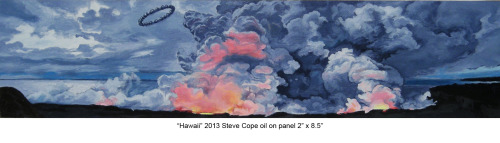

Above, Hawaii, 2″ x 8.5″ oil on panel 2012

The collective and invented memory of landscape.

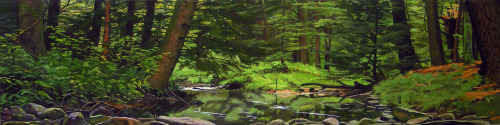

Wissahickon, 7″ x 28″ oil on panel 2015

Steve and I met in Normandy, France where we studied landscape painting with the formidable Jason Berger. Decades later we have reconnected, I’m happy to say. And though I moved into more of a performative and writing life – Steve is still deeply painting. He is a Professor of Art at Saint Joseph’s University and his work has been featured in many solo and group shows, and is collected in both private and public collections. These days I’ve been in research mode around process and protocols with making work. Having looked at and admired Steve’s work for a long time now, I was grateful for the opportunity to sit down and talk to him about it.

Oh, and thrilled to say that I am the proud owner of one of his paintings. I love living with it.

Point Of Departure

Old Men, 5″ x 20″ oil on panel 2014

SC: Before I started painting these landscapes, which was not that long ago – 2007, 2008 – I was painting big, drippy geometric abstractions. And in the studio there was a little block of wood, 1’ x 5’ inches, I drew a little landscape on it. I thought well, that’s sort of interesting. The vastness of that space just got amplified. That’s what really started me on this – something so vast on something so small.

DV: Is there a an issue in the work that you’re dealing with right now that you’d like to centralize this conversation about?

SC: If I think about what I’m doing now, it’s a matter of putting together a composite image that I hope looks beautiful and intriguing to the viewer, it’s as straightforward as that. I like a deep space landscape and I want it to look like it makes sense even though it’s a bunch of different places all put together.

So step one is putting that image together. I do that using drawings and Photoshop, with many different photos, and I print it out when I’m happy with it. It is a compound image, it’s not actually a real place. The sources I work from look a bit choppy, but in my minds eye I think that these elements are going to look seamless when I paint them. In the process of painting, I also change things, move things and simply make up things as I go. Recently I have been adding in quotes or forms from the Hudson River School paintings, trees and such, as a nod to how great they are and to their influence.

Painting The Paintings

DV: What are your materials – how do you paint them?

SC: I use oil paint and pencil on these custom birch ply panels. To make them, I use powerful work lights, and super strong reading glasses. The brushes are tapered and pointed almost like needles.

DV: The smaller images were mostly 2″ x 8″ and the newer pieces are 7″ x 28″. Why do you think they’re getting larger now?

SC: I just need more room. I was making the little ones and getting a certain amount of detail, I just want to put more. I feel like the more I touch the object with my paintbrush the more connected I get to it, and the better it gets. So the larger panels just allow me to have more time with those paintings, to touch them more often for a longer duration. So I get more and more connected to them.

They start really chaotic. I have a photograph that is like a Frankenstein image, I do base coats of color dropped into broader areas. Then the next step for me is to find anchors in the image. So I’ll paint an area to completion – say two square inches or three square inches of a spot, it could be a rock or a tree, just something to anchor that area in the painting then I move out from that spot and organize all of that chaos into something that’s recognizable and hopefully good looking.

Construction

Split, 7″ x 28″ oil on panel 2015

DV: Is the process of reconstructing these base elements of space, time and geographies into new ecologies present in previous works, or are they exclusive to these landscape paintings?

SC: In the beginning I would simply take photographs or acquire photos from friends, family or students and I would paint straight ahead. And then I found that if the photograph wasn’t enough I would add a form to it and that became interesting. I would add a rock or a tree, now I’m adding whole sections of the landscape, I’m renovating the whole space and all the objects in it to an order that I like and that I think looks interesting. Sometimes you have a landscape and it just doesn’t overlap well. You can’t get from one place or another and it just is not as interesting as it could be. To find that perfect spot on the earth is hard, I want to develop the space well, so that it has patterns and pathways, contrasting areas and dynamic movement, beautiful light. Size relationships, I can control that, I can control how far you get into the landscape before you hit something else. So I can dictate in a certain way, how your eye travels through that space.

DV: There’s a rate of entry, there’s a whole sequential pathway. It makes me think about the scale of the paintings and what that means to the viewer. I’ve been looking at them for a long time and now that they’re getting bigger, I’m allowed to get closer.

SC: And hopefully you see more stuff. Also you know, there are places in the paintings where I can make a little separate thing, like little vignettes. So, on the left side there’s an area with rocks and a broken down tree in a stream, that whole area separates itself as it’s own little painting off on the side. I can do that in a couple of places in the painting, I’ve got these separate little spaces that on their own may be engaging. They read in with the whole, but at the same time there’s this gathering here and I can read it as a separate little idea.

DV: They’re like time zones, or signatures – like sub-spatial occupations. These spaces have delicate harmonic qualities that yield subtext. Ha – the subtitles of space.

SC: Yes, also some of the same trees or forms show up in a bunch of paintings…because I like the tree, or the bark or something about it. That’s kind of fun because I have a series of forms I can use multiple times in different paintings.

DV: Well it’s also, in a subtle way making them into a series – a serial format – and that’s such a modern idea with painting and when you see these repeating elements that you develop a sense of history with and then they end up in a different space and time and they echo and the narrative stretches. Italo Calvino talks about a “magical” object inside of story that travels though it – a ring for example – it moves through the story as a conductor of the story dragging and rendering these invisible force fields that ultimately become the story itself. When I looked at your earlier paintings with the hoop motif that came to mind.

Chronic Invention

DV: The paintings are getting slightly larger in scale, is there anything that you’re wrestling within them that feels new?

SC: Almost every time I have to learn a new way of doing something because they’re all so different. I mean the thing that I wrestle with all the time is, how am I going to paint this. I’ll put together this photograph and I’ll sit down with this big white panel there and this photograph here and I look at that image and think how the heck am I going to do that? So I feel that I’m painting at the very top edge of my capabilities. I barely think I’m going to pull this thing off every time. I’m not sure I can paint that thing…I mean…grass…c’mon. I want them to look seamless. I want them to look like a real place even though it’s not.

DV: Even though it’s not, and even though it is.

SC: And I think you can probably pick that up.

DV: There’s a push and pull. These paintings do their own math – the seemingly desperate parts, or states or elements are conjugating themselves. Seems like these worlds are in a flux between two things – real and not real – I sense this tension and also an energy to become real.

SC: I want them to look sort of like earth, but you’re looking through a window that’s not exactly our place.

DV: That’s what strikes me so much about them, because when I look at them I get all of the articulation, all of the reference of places known and unknown – but for all of the work and the rigor it’s almost as if the painting isn’t about the landscape, it’s about those subtle things that are indicated by the relational value of the parts. Relativity. That’s super interesting, and that’s where they get bigger, that’s a big idea in a very small painting.

SC: And I’m a painter, and I want to paint.

DV: They’re conceptual paintings.

SC: That’s great, that’s how it feels to me.

DV: There’s a real something there that can’t be identified, metaphysical maybe? Yeah conceptual, but isn’t everything anyway.

SC: It’s sort of a ridiculous idea to build this space into something flat. It goes through a lot of filters before it becomes this visual thing. I’m using these different light sources, putting all these different fragments from different photographs from different places that can be wildly far apart – California to New York.

DV: These tensions create an energized communication within the work. I was wondering if you feel the paintings are evolving process wise.

SC: They’re just bigger and more complicated, there’s just more stuff in them for me. So the size they are right now is big for me – 7″ x 28″ inches. I can’t see it getting smaller or bigger.

Vista

Flow, 7″ x 28″ oil on panel 2015

DV: When you’re painting these do you feel like you’re painting the end of this idea?

SC: I don’t know. This still feels pretty new to me. For this size (7″ x 28″) I haven’t made very many. Some of the 5’ by 20 inches maybe I have fifteen. They still feel pretty young right now.

DV: So you said the titles are a little more vague?

SC: Yeah, they’re pretty ambiguous these days. In the beginning when I was making the smaller ones, because they weren’t altered as much, I would name them as place. Connecticut or Rangley Lake in Maine. But now I can’t do that because there are too many sources.

DV: Can you give me an example of a good vague title that you like?

SC: “Divide” is good, others are “Split” and “Merge”. I’d like the title to lead the viewer just a bit.

Reach

Divide, 7″ x 28″ oil on panel 2015

DV: What are these larger paintings teaching you – what are you learning from them?

SC: Getting the image right in the beginning is really an intuitive thing. The painting of it is very concrete and technical, so there’s these two different ways of getting to the end. They’re hard enough that I’m just barely making them, and that feels good. It feels like I’m really reaching.

DV: What’s the reach and what’s the demand?

SC: To make these things so that they’re not wonky looking, the craft of the thing and the skill of the thing has to be at a certain level, it’s really hard for me to do that. I hadn’t been trained to paint this way and I had to figure out how to do it on my own. It wasn’t that I wanted to be a better painter as much as that’s what the image was going to take – if it was going to be interesting then I had to do it this way, it wasn’t a natural thing for me. It’s still not. So my capabilities had to get better. I didn’t show anybody these things for a long time because they weren’t very good.

DV: So the idea was there and you had to climb it.

SC: Yeah, I had to get to it. And now they’re big, and now they’re really exposing.

DV: I identify strongly with the process you described – delay and visibility. Having recently finished writing a book, I had to figure out how to construct it – I went into a room for six years. It felt good and damned difficult, like it was painting. And as you referenced, the process demanded me to function at the top of my capabilities – known and unknown. There is a confidence there, but the climb is incredibly steep.

SC: It’s like that Dorothy Parker quote, “I hate to write but I love to have written.” – cause it’s not fun in the middle. It’s a pain in the neck man and sometimes it looks like hell. Then finally you get a little anchor and you think I actually can do this.

DV: Paintings, all work can create a deadness when you’re not collaborating with them well enough, they’ll tell you. And conversely, there’s a click when it swings and gets sparkly and then you can’t even remember how you executed it.

SC: At a certain point you know it’s doable. which is good when you are going to spend a lot of hours on that canvas.

DV: Reminds me of you saying, “I need to make a compelling image and lock that into paint.” Are you still in agreement with that?

SC: This idea of locking into paint is a phrase that I heard Graham Nickson say, who is a great painter and teacher. It took me a little while to figure it out, but there’s something about when you paint, you lock the moment in forever. When you go back and look at a Rembrandt you somehow feel that era.

DV: Time.

SC: It locks it in there, it seals it in forever. So on top of locking the landscape into the image which is true, it is also a kind of a time capsule. You look at those Rauschenberg’s and it’s 1965, or you look at that 1925 painting Birth of the World by Miro in that world of modernism, and you can feel the moment in the image.

Sight Criteria

DV: Do you feel that your students are different creatures because they have been raised inside the world of two dimensional screens with it’s own ecology, languages and behavior. Has this effected how they see and the experience of that engagement?

SC: They don’t realize they have eyeballs. They use their eyes to navigate, most don’t see deeply and fail to have a rich visual experience. We tend to save our visual experiences for places that we know are beautiful, and they are but these experiences are around us all that time and that experience is continuous. There may be beauty in the shadow under your car as much as there is in the Grand Canyon.

DV: There is such a drive to capture an image of that shadow instead of sitting with it. Images seem to be disposable, collected with not much revisiting.

And with your paintings there is a big, beautiful contradiction. You start off with acquisition and hybridizing images, but then the body of the image gets built back into life. There’s a race against itself to become real – into this poetic thing, locked into paint.

DV: Steve, it’s been great to speak with you.

SC: It’s been entirely my pleasure and privilege. Thank you for your insight and generosity.

Steve Cope lives and paints in New York City. He is an Assistant Professor of Art at Saint Joseph’s University.

Representation:

Downing Yudain LLC

Lily DeJongh Downing

357 Old Long Ridge Road

North Stamford CT 06903

Office: 203-355-2718

Email: info@art357.com

Schmidt-Dean Gallery

Christopher Schmidt

1719 Chestnut Street

Philadelphia, PA 19103

215-569-9433

This article was first seen on my monthly newsletter, hop on.

let's JOIN FORCES

Join the newsletter.

Support is on the way!

Seasoned Artist. Idea Jockey. Author, NYC.

Seasoned Artist. Idea Jockey. Author, NYC.